Not Your Hospital's Precedex: Why Street Medetomidine Hits Different

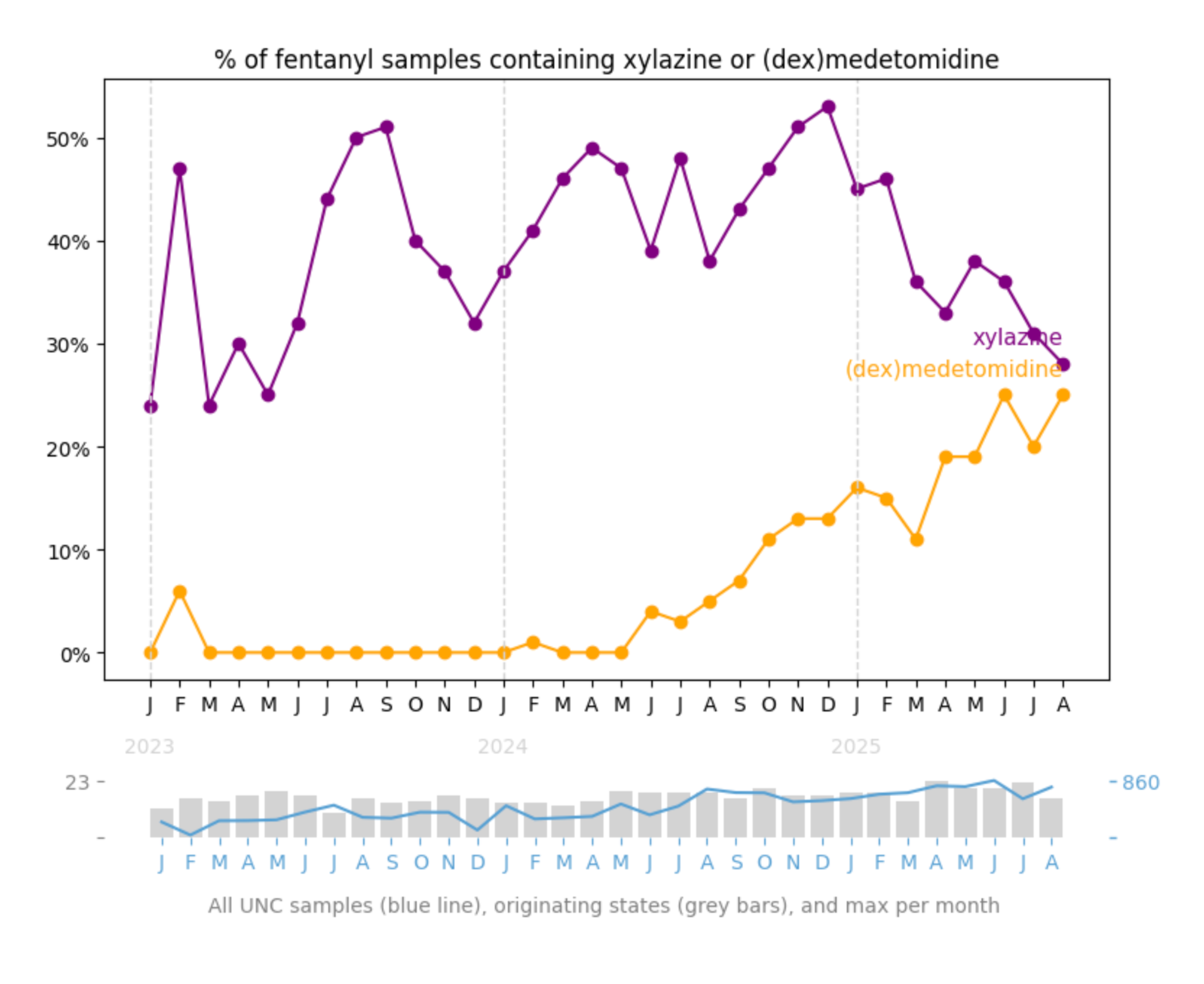

If you follow our watchlist, you know about a veterinary tranquilizer that's recently entered the unregulated drug supply in multiple states. No, not xylazine, though we're still keeping an eye on that. Think even more recently. The substance is medetomidine, xylazine's mysterious and nefarious cousin. A potent sedative and alpha-2 agonist, medetomidine first showed up as a blip in our data in late 2022 and really started trending up last summer.

Unlike xylazine, medetomidine (in a form called dexmedetomidine, brand name Precedex) is FDA-approved in humans. In fact, it's commonly used in hospital settings as a sedative and analgesic. Babies on ventilators. Adverse clinical reactions won't surprise you: lowered pulse and blood pressure. Sure, that comes with the territory of depressants. Overall, the drug has been hailed for its margin of safety – as safe as safe can be, according to some scientists.

But that's with known doses, in controlled environments.

On the street, medetomidine tells a completely different story.

Our new research study reveals that medetomidine – which we've identified in 14 states – is causing intense, unexpected hallucinations. Among 11,000+ samples analyzed, samples containing medetomidine were 12 times more likely to be associated with hallucinations than other samples.

People described these hallucinations as "intense," "trippy like DMT," and "psychedelic." Some reported visual and auditory hallucinations followed by passing out. Others experienced vivid nightmares lasting 8 hours or dissociative effects.

The rub? Precedex is actually used to prevent delirium in clinical settings.

This stark contrast highlights how context transforms a drug's effects. Street exposure differs fundamentally from medical use: doses are unknown and potentially massive, there's no titration to effect, consumption is chronic rather than acute, and the drug appears in chaotic, unpredictable mixtures – in this case, averaging 8 substances per sample (commonly including fentanyl and/or xylazine).

For harm reduction workers and people who use drugs, unexpected hallucinations might serve as an early warning – similar to how persistent wounds signaled xylazine's arrival. (In contrast, opioids don't cause hallucinations.) Our drug checking partners found medetomidine commonly appears with fentanyl (59%) and/or xylazine (56%), usually in white powders.

About Our Investigation

We first saw medetomidine in our service in October 2022 in a sample from Raleigh. We mostly see it in East Coast samples, some from the Midwest. Here are all our medetomidine samples. More recently, we were asked by community members in Pittsburgh what could be causing a sudden uptick in hallucinations. Even though our drug checking is a service, not a research study, we thought our data could help. So we pre-registered the investigation and let y'all know about it in our newsletter. In addition to community partners (Alice Bell), we also tapped the expertise of anesthesiologists who uses the medication in the hospital (Irina Philips and Brooke Chidgey), a lab scientist (Madigan Bedard) who uses it in animal studies, and a drug checking stats expert (Sam Tobias). Dream team! For the drug checking data nerds, we were careful in our use of statistical models, and would love your feedback.

The mechanism behind these hallucinations remains unclear. Street medetomidine might contain both active and "inactive" forms of the drug (unlike pharmaceutical versions). People tolerant to opioids might be desensitized to sedation while remaining vulnerable to other effects. Or the sheer dose could be orders of magnitude beyond therapeutic levels.

What's certain is that medetomidine adds another layer of complexity to an already hazardous drug supply. Like xylazine, it likely doesn't respond to naloxone in the same way, though naloxone should still be administered for suspected opioid overdoses. And rescue breathing becomes especially critical when veterinary tranquilizers are involved.

Dexmedetomidine also plays an import role in biomedical research and pharmaceutical drug discovery, as it's the go-to anesthetic of choice in animal model lab science.

We learn more about medetomidine every day. Our harm reduction partners in Pennsylvania – now corroborated by CDC data – warn that medetomidine is causing severe and potentially life-threatening high blood pressure if you stop taking them abruptly. Other withdrawal symptoms reported describe tachycardia, hypertension, extreme agitation, tremors, and vomiting that can last for days. Unlike opioid withdrawal which is rarely fatal, withdrawal from alpha-2 agonists like medetomidine can cause dangerous cardiovascular instability requiring medical management. Healthcare providers may not recognize these symptoms as distinct from opioid withdrawal, potentially missing critical intervention windows.

If you work with people who use drugs, especially fentanyl, we encourage you to ask about recent changes or concerns, especially new and unexpected sensations. The word on xylazine was 20 years too late. We can do better this time.

Same substance, radically different outcomes. This is what happens when pharmaceuticals enter the unregulated drug supply – precise medicines become chaotic adulterants, and safety profiles written in controlled settings become less meaningful on the street.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Department of Chemistry Mass Spectrometry Core Laboratory for mass spectral analysis of drug samples. Chemical analysis was conducted by Erin Tracy and Jalice Manso. Thank you to additional program staff involved in operations: Shay Louis, Natalie Sutton, Illyana Massey, Colin Miller, David Marshall, Dmitri Fisher, LaMonda Sykes and Bridgette Mountain.